Wee History of Burns Night

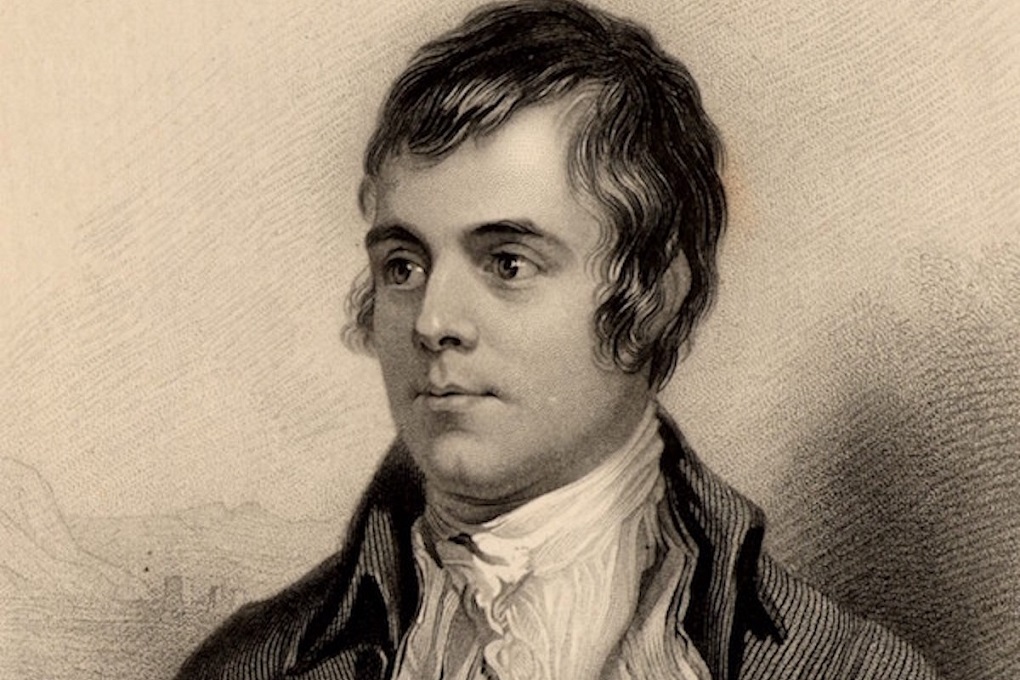

Like Christmas, in simple terms Burns Night is a great big birthday bash. We celebrate it just one month later, a silver lining in deep winter on 25 January – the day Scotland’s pre-eminent poet, Robert ‘Rabbie’ Burns, was born – and it’s similarly indulgent and alcohol-infused. But it’s also ostentatiously Scottish and all the more rigorously traditional for it.

Plus, its origins are more sober. The first Burns supper would have had quite a different atmosphere, not least because it was held on a warm midsummer’s night in July 1801. In a snug little cottage in Alloway – Burns’ family home – nine of Burns’ close friends gathered to mark the fifth anniversary of their friend’s death. The organizer of this commemorative dinner, Reverend Hamilton Paul, kept notes of the occasion, proof that – with the exception of a toasted sheep’s head, which we’re rather glad has been cut from the menu since – today’s line up of recitations and rituals has barely changed in 200 years.

Traditionally, the host begins proceedings by saying Selkirk Grace, which was written by Burns and believed to have been first read by the Earl of Selkirk: “Some hae meat and canna eat/ And some wad eat that want it;/ But we hae meat, and we can eat,/ Sae let the Lord be thankit.”

The haggis is then piped in on a silver platter (or some such showy crockery) and one chosen speaker, esteemed, Scottish or simply brave enough, will perform the Address to a Haggis with as much gusto as possible so as not to bore the guests with its eight verses of hard-to-understand Scots dialect. The theatrical piercing of the haggis with a ceremonial knife is sure to get their attention. The first dram of the night and a communal chorus of the Haggis is your signal to tuck in to the “great chieftain o the puddin’ race”, accompanied by mashed neeps (turnips) and tatties (potatoes). Many more whiskies may follow, often as way of toasting each speech. Rabbie, who penned that “Freedom and whisky gang thegither”, would surely approve.

The second integral speech to be performed on the night is the Immortal Memory, which not only praises Burns’ legacy but Scotland as a whole. The Toast to the Lassies is a more recent but popular mid-meal hiatus. Burns Night would have once been an exclusively male affair, so this toast was introduced about 70 years ago to thank the women for cooking. Fortunately, it has now evolved and survives only as a humorous meditation on gender, which is followed by a female attendee’s Reply to the Laddies. The end of the meal prompts the host’s Vote of Thanks and the night reaches a rousing conclusion with a whole-party rendition of Burns’ Auld Lang Syne, which was often the parting call at gatherings in Burns’ day. Its lyrics emphasise the importance of long-lasting friendship; a fitting end to a tradition that began by bringing friends – both living and lost – together, and continues to do so to this day.

It is no surprise that this winning formula – poetry, a hearty meal and good company – cooked up by Burns’ friends more than two centuries ago has stood the test of time. Just one year after the debut dinner, a number of informal Burns clubs had sprung up in nearby Paisley and Greenock to pay tribute to Rabbie’s life and work on his birthday (or at least what they thought was his birthday – they were four days late). The rest of Scotland and Britain soon followed suit and now there are more than 250 official Burns clubs globally. Appetite for Burns supper shows no sign of abating, having grown to symbolize all that is great about Scotland, offal and all.

Article Credit: Jenny Rowe – Scotland Magazine – https://www.scotlandmag.com/burns-night-history/

Photo Credit – The Rake

Photo Credit – Forbes

Photo Credit – STAY Central Hotel

Photo Credit – Daily Express

Photo Credit – Hilton Glasgow

Photo Credit – iStock